Sometimes science can teach us powerful spiritual lessons if we are open to understanding science in a personal, subjective way. That is not to say to that the purpose of science is to increase our spiritual understanding, and we must not allow our personal subjective experience interfere with the proper objectivity needed for good science. Rather, once completed, the body of scientific research can be a source of inspiration, and can help us appreciate the creation in which we live.

I’ve had the great privilege of teaching in the Psychology Department of Columbia University, and the first class I taught was on sensation and perception; my qualifications for that coming from my training in research on the perception of time. Even before I started studying Kabbalah at the Kabbalah Centre, one theme in that course struck me as profound. That theme was the extent to which our personal experience is constructed, and only indirectly influenced by the objective world. As it turns out, this theme is central to the study of Kabbalah as well.

Among the first things I would tell my perception and sensation students is the definition of illusion, and their importance. “Illusions are errors in perception that occur in all sense modalities. They provide proof of the indirect relation between the physical world and the mental representation of the world .” This information is so important that I repeat it over and over, and tell them that it will have to repeat it verbatim on the midterm. Why such emphasis on a phenomenon, that while curious, hardly seems central to human understanding? Well as it turns out these curious errors in perception are indicative of a fundamental and counterintuitive fact about human experience; our experience of the world is not direct, but rather constructed. Swirl that around in your mouth for a bit while I explain.

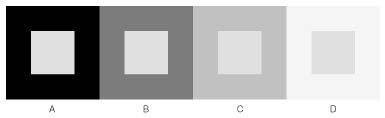

Lets look at a simple illusion, such as the one to the right. The figure is composed of eight squares, four small ones inside of four larger ones, each with a different shade of gray. Which center square is darkest? Most people say “D.” In fact all four center squares are exactly the same shade of gray. You can prove it to yourself by masking the image so you can only see the center square. This figure demonstrates that even simple features of images, so-called visual primitives are not derived directly from the image. In fact we know that brightness perception (how black or white a bit of image appears) depends on ratio of intensity of a bit of image and whatever surrounds it. It’s the way our nervous system has evolved to deal with different lighting conditions. This system insures brightness constancy (the appearance of grays don’t change) when light sources are very bright or very dark.

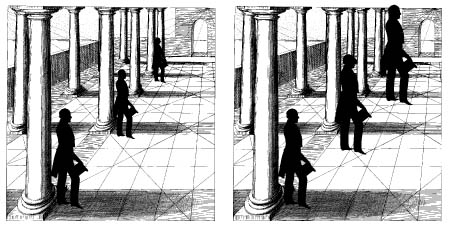

Now consider the considerably more sophisticated illusion shown at left. This image gives an impression of depth even though it is quite obviously two-dimensional. In fact the illusion is so powerful and so common that we don’t even really think of such images as illusions. Really there are several techniques that convey the sensation of depth in flat images like photos and paintings. Those techniques include, lines converging towards a point (linear perspective), patterns changing in size, and height on the plane (parts of the picture near the top seem further away). The figures of people illustrate the powerful relative size illusion. The people in the left panel are drawn so their heads and feet fall on lines converging on a central point, and so we perceive them as equal in size, but differing in distance from us. The panel at left shows what happens if we draw the people with equal absolute size. The person on the upper right appears as a giant because of the powerful depth cues. The point of this demonstration is to show how simple configurations of lines and patterns can completely fool us into perceiving something quite complex, like space. The constructive nature of perception is not constrained to simple features.

Finally consider the figure to the right. The is a diagram of an illusion, not an illusion itself. To witness the “flash lag” illusion, you need moving objects, so a description will have to do. If you have a wheel with a light attached to it, spinning against a wall with a second light attached to it, you can spin the wheel, and flash the lights at the same time. Pick the right kind of lights and spin the wheel very, very slowly and you’ll experience a single bar flashing, as shown in panel “A.” Speed up the bar and you, as in panel “B”, and the fixed bar appears to progress in the direction opposite the wheel’s. The explanation for this phenomenon is quite different from the last two illusion. The reason you perceive the bars as separating is because your nervous system is actually anticipating where the bar will be when it flashes, otherwise the delay in processing information in your nervous system would cause you to see the bar on the wheel in panel “A” flash past the fixed bar. As the wheel speeds up errors creep into your brain’s prediction of the motion, but that error is applied to the fixed light, because your brain “knows” where the light on the wheel should have flashed, and makes your perceive the flash in that location. Unbelievable; your brain lies to itself to patch up errors it makes in understanding the world!

These several examples all tell us the same story; our perception of the world is not direct. Our perception doesn’t work like a camera, simply recording whatever hits our sensitive spots. On the contrary, our perception is constructed, and our experience is mostly our brain’s guesses about what’s out in the world. Those guesses are necessary because we often need to work fast and in the absence of total information. Those guesses are however usually correct. For example, When lecturing I often stand behind a podium. I ask the students if anyone thinks my legs aren’t their just because they can’t see them? Look around now. See if you can count how many objects are partially obscured by other objects. The light from those objects is incomplete, but you perceive them as complete. This is constructive perception working properly; illusions are just the exceptions that demonstrate the rules.

Now what does all of this have to do with spirituality or Kabbalah. As I started to teach perception I became more and more amazed that science demonstrated that my experience that seems so real has more in common with illusion that with photography, in the sense that it is constructed. Perception creates a theatre in which I can act. My actions change the world and my perception updates my theatre, usually correctly, sometimes not. How wonderous! I had an emotional reaction to this. This is what science can do for us – provide us with knowledge to which we may react with wonder. Cosmologist wonder at the grandeur of the universe; quantum physicists at the weirdness of the world in miniature. Psychologists get to wonder at us. That wonder is not science, it’s a subjective, evaluative reaction, that can lead us to appreciate the world in which we live. For me this is the beginning of a spiritual life.

For Kabbalists, appreciation is a gateway to a closer relationship with the creator. Of course one may wonder without believing in a creator, but if one happens to believe in the creator than appreciation helps us understand its nature. Kabbalists are also the best psychologists I know. The writings of Kabbalah (the spiritual system I’m most familiar with) are replete with warnings not to take the evidence of the five senses two seriously. Beyond perception lies and infinite and subtle world of true cause and effect, they claimed, based on their own wisdom and experience. It just took science a few millennia to catch up.

Note: Figures taken from Coren, Ward and Enns, “Sensation and Perception,” 3rd Ed.

[…] not physical, and if it’s not physical than it’s not real. This seems airtight, but things are not always as they seem. There is a hidden assumption here, namely that the laws of gravity are to be assumed and not […]